Spoiler—this crypto dispute ends in a draw. In these week’s coverage of the ongoing encryption debate, both sides are almost right enough. The DoD and the FBI hashed it out at a House Committee Meeting last week with former FBI counsel Jim Baker speaking out against the party line at an American University cyber conference that same day. An old bit of technology was brought out of the shadows to remind us what happened the last time we tried to implement backdoors, and Firefox isn’t taking any chances. With the new rollout of Firefox 74, you may no longer be able to access some of your favorite sites—and for good reason. As the world tries to stay safe—one country, party and browser at a time—the encryption debate might touch more entities than it leaves out.

Why the Clipper chip could teach us a lesson (or not) about encryption backdoors

Remember that program in the early 90’s when the FBI made a built-in backdoor chip that soon became outmoded and eventually faded into obscurity? Neither do most people. But if ever we should, the time is now.

Why? Because it could happen again. The legacy of the Clipper chip (FBI, circa 1993-1996) is that it failed for all the right reasons. Initially a chip pairing, one 80-bit (yes) chip was literally baked into the hardware and the other chip was held in escrow for the FBI to use should decryption become warrant-necessary. The Diffie-Hellman key exchange was used between the devices.

The problem was that technology was advancing at such a rapid rate that physical encryption securities soon became outstripped in the wake of relevant software solutions. The keys and bits simply couldn’t hold up for long enough. Also, a key pairing always risks being found by bad actors, be it physical or digital. Plus, the escrow design incidentally had a fatal flaw that was reported in 1994 and helped cement its demise.

So why are we going over this now? According to Matt Blaze, McDevitt Professor of Computer Science and Law at Georgetown (and finder of the fatal flaw), the decisions to legislate backdoors are as shortsighted now as they were in 1993. Any attempt to legislate technology in writing will only be rendered irrelevant shortly as we continue to crack ever harder encryption schemes, (and now careen towards quantum readiness). It’s almost as hard now, if not harder, than it was 30 years ago.

"The FBI is the only organization on Earth complaining that computer security is too good,” Blaze says - and it may be due to the botched attempts of backdoors that it’s stayed that way.

Related posts

- Battle of the Backdoors in Networking Infrastructure: Intentional vs. Incidental

- Going Undetected: How Cybercriminals, Hacktivists, and Nation States Misuse Digital Certificates

- 86% of IT Security Professionals Say the World Is in a Cyber War

Firefox no longer acknowledges TLS 1.0 or 1.1

In case you don’t know what’s best for you, Firefox does. And now it’s time to prove it.

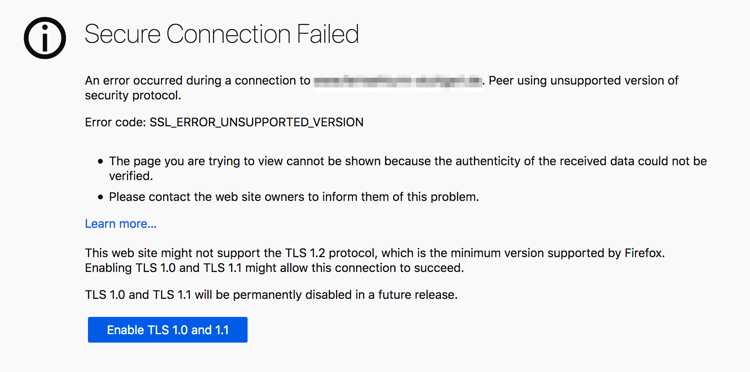

Back in October of 2018, Mozilla warned that they were moving to TLS 1.2 as the new threshold for security on their browser. Firefox Nightly and Firefox 73 have now rolled out the heavy hammer - sites that have not yet upgraded will be replaced by this sign every time a user wants to connect:

We know TLS 1.0 and 1.1 have been exploited for their flaws, with embarrassing attacks like POODLE and CRIME to show for it. Now, as TLS (the next generation of SSL encryption on the web) enters a new era, those previous versions will no longer be supported by default.

Depending on what version of Firefox you’re using, you may be safe for now, but Firefox 74 ships on March 10th - with TLS 1.2 being the absolute lowest threshold necessary to ride. There will however be an opt-out button, but according to Mozilla’s blog, it may not be around for long.

Friends don’t let friends use TLS 1.0 or 1.1. And neither does Firefox.

Related posts

- Google Has Increased HTTPS Use. Is That Enough?

- How Does a Browser Trust a Certificate?

- Why Are You Ignoring That Browser SSL Certificate Warning?

Are the FBI and DoD at odds in the encryption debate?

“It seems from the various statements we’ve seen that the FBI is taking one position and the Department of Defense is taking the opposite position” said House Committee Chairman Jerry Nadler, D-N.Y. to Christopher Wray at a Committee hearing February 5

And he may not be wrong.

In October of last year, Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif. sent a letter to Senator Lindsay Graham on the support of end-to-end encryption by the DoD’s CIO Dana Deasy. Concluded Deasy, “The Department believes maintaining a domestic climate for state-of-the-art security and encryption is critical to the protection of our national security.” It makes sense to protect the supply chain that protects the American people. The same companies that could be forced to provide backdoors could also be places of critical infrastructure—think of all the upstream technology clients that supply airports, dams and defense contractors.

Arguments against were also presented, like this one from Rep. Henry Johnson, D-Ga.;

“When it comes to domestic terrorism and hate crimes and right-wing extremist nationalist groups, antisemitic groups out here using encryption to organize, to plan and then to conduct operations that actually result in people being killed and injured and you’re doing it in a way that you cannot be surveilled, you cannot be held to account in any way after the fact for what you did, I think that is a danger to our society.”

And he may not be wrong either. But the issue might be more complex than “mass underground crime vs a completely safe alternative.” The potential ills on the other hand could include surveillance by hostile governments, political snooping, the ‘killing and injury’ of human rights activists and the tracking and internment of ethnic minorities like the Uygars in China. We’ve seen this sword cut both ways.

In his testimony, Wray avoided use of the word “backdoor,” even adding, “I would tell this committee the FBI believes strongly in encryption. We, after all, have a cybersecurity mission.”

He called on lawmakers to “seek a solution that allows us to protect our nations’ most vulnerable while at the same time addressing the equities of the larger national security community.”

Wray also points to Australia’s recent backdoor laws to back his point, (which may not be advisable right now).

"I reject the possibility that this isn't doable," asserted Darrin Jones, Assistant Director for the FBI's Information Technology Infrastructure Division.

Not everyone agrees.

Jim Baker, former counsel for the FBI, wrote in an essay last October “I am unaware of a technical solution that will effectively and simultaneously reconcile all of the societal interests at stake in the encryption debate, such as public safety, cybersecurity and privacy as well as simultaneously fostering innovation and the economic competitiveness of American companies in a global marketplace.” It seems that even the FBI is at a divide on this one.

Possible solutions have been brought forward, such as the one by former Microsoft CTO Ray Ozzie in which private and public keys would be created for each device, with only law enforcement having access to the private key stash which they could use solely in conjunction with keys from the user or vendor. However, much like in the Clipper fiasco, the issue was raised as to how to protect that private key stash from infiltration by bad actors.

Said Jim Baker at the American University Justice in Cyberspace conference, "It just doesn't exist, and I think it's kind of magical thinking to expect that companies are going to just come up with a solution in that regard."

Related posts

Why Do You Need a Control Plane for Machine Identities?

2024 Machine Identity Management Summit

Help us forge a new era of cybersecurity

Looking to vulcanize your security with an identity-first strategy? Register today and save up to $100 with exclusive deals. But hurry, this sale won't last!